- Ziggurat Realestatecorp

- Jul 27, 2025

- 6 min read

Companies like Compass, Rocket, and Zillow are trying to create one-stop shopping venues.

The housing market is barreling toward its third bad year of home sales. Once demand roars back, real estate transactions could look different for buyers, sellers, and investors. Anemic home sales are accelerating a housing market reconfiguration long in the making. In the coming years, it may be more common to purchase a home from one of the big public builders than a local developer, or secure a mortgage from the same portal you used when shopping for a home.

Big real estate companies are building digital platforms to keep more parts of the home purchase transaction under one roof—and taking business from real estate brokerages and mortgage lenders. “Anything that makes things easier for people—that’s where the world is moving,” says Tim Bodner, PwC’s real estate deals leader.

The fight for dominance recently spilled into the courts. Compass, the largest U.S. brokerage by sales volume, sued listings portal Zillow Group over new rules regarding listings that are initially viewable only by its agents and their clients. The lawsuit isn’t just a fight over wonky listing rules, but a conflict about the shape of the future housing market.

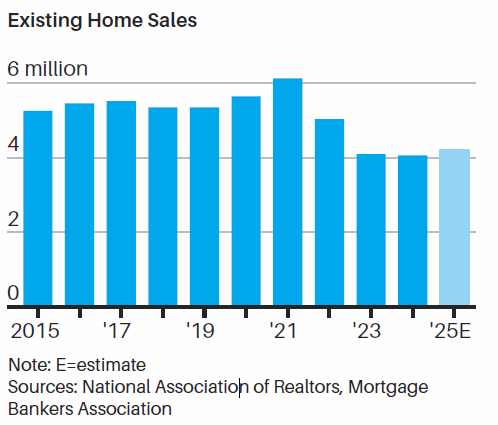

Consumers have been backing away from buying a home for several years. The number of existing homes sold fell to nearly 30-year lows in both 2023 and 2024. In the first five months of 2025, homes sold at an average seasonally adjusted annual rate of about 4.1 million, down from more than six million as recently as 2021, according to National Association of Realtors data.

The whole sector is under pressure until sales climb to at least five million, says Leo Pareja, CEO of brokerage eXp Realty. That’s far away: The Mortgage Bankers Association expects existing home sales to ramp up in the coming years but to remain below five million through 2027, as prices hold firm and mortgage rates remain above 6%. The path ahead for consumers will look increasingly streamlined—and is rife with both opportunities and risks.

Shifting Winds

It isn’t just buyers and sellers backing out of the market. The National Association of Realtors, the industry’s largest trade group, is budgeting for its membership to decline to 1.2 million in 2026, from nearly 1.6 million as recently as 2022. That’s in part “due to the housing market’s current headwinds,” a NAR spokesperson says.

“There’s going to be sort of a reckoning” if sales remain slow, says Columbia Business School professor of real estate Stijn Van Nieuwerburgh. “Probably a bunch of people are going to quit this profession altogether.” Where some smaller brokerages see trouble, others see buying opportunities. Compass, a $3.2 billion real estate brokerage based in New York, grew its ranks of principal agents nearly 42% in this year’s first quarter from the year prior, largely because of its acquisitions. “Most brokerages are really struggling financially,” says Rory Golod, Compass’ president of growth and communications. “They don’t have the size, the scale, and sort of the balance sheet to get through this.”

Consolidation is coming to homebuilding, too. At a time when more builders are offering buyer incentives or slashing prices, the big players’ economies of scale allow them to keep costs lower. “In a slower and choppier market, mergers and acquisitions get more common,” says Ali Wolf, chief economist of real estate research firm Zonda. Publicly traded home builders comprised 52% of all new home sales in 2024, a larger share than anytime since at least 2005, Zonda data show. That could rise as high as 65% in the future, says Wolf.

Perhaps most emblematic of where housing is headed is the coming unification of Rocket, the nonbank lender best known for mortgage origination, with mortgage servicer Mr. Cooper and brokerage and home-listing portal Redfin. The three companies “realize that we are stronger together than we would be apart,” says Varun Krishna, Rocket’s CEO. The combined company will be the largest mortgage servicer and second largest lender in the U.S., according to Inside Mortgage Finance data. Redfin, meanwhile, gives them “the brand name and real estate brokerage that they never had before,” says Wedbush Securities analyst Jay McCanless.

Across categories, consumers now expect a more personalized experience, says David Steinbach, global chief investment officer of Hines, a real estate investment manager with $90 billion in assets. “That consumer taste for a better service, better outcome— which only data can do—means the scaled groups are going to win. The big are going to need to get bigger in order to better serve the needs.”

The Future

Companies that derive earnings from the homebuying process—such as listing portals, mortgage companies, and brokerages—have long looked for ways to capture a bigger slice of the pie in a fractured housing market. They may have finally settled on a recipe.

Zillow emerged from the 2021 failure of its volatile business buying and selling homes with a new plan: build a “housing super app” offering a range of housing services to buyers, sellers, renters, and agents in one place.

It hasn’t been a smooth ride. Zillow stock is down 5% this year, and 65% below its pandemic high-water mark. But its push to integrate mortgages— whether through a mortgage marketplace or a lending arm of its own—into the buyer experience, along with investments in rentals and tools for agents, is finally paying off.

Zillow expects to be profitable under generally accepted accounting principles in 2025 for the first time since 2012. “The silver lining of a bad macro is it forces you to really be crisp about what’s working and what’s not working,” says Zillow CEO Jeremy Wacksman.

In the company’s super-app future, the homebuying transaction will never leave the company’s orbit. The whole process—shopping, hiring and communicating with an agent, talking to a loan officer, making an offer, getting a mortgage, and closing—will happen “in the palm of your hand inside an app like Zillow,”Wacksman says.

Across the spectrum, big players in real estate are envisioning what a less fractured housing transaction looks like. Buyers shopping with a Compass agent now have access to a dashboard to keep track of their communication, forms, to-dos, and referrals.

Realtor.com—a home-listings portal run by Move, which, like Barron’s, is owned by News Corp—sees an opportunity “to create an open marketplace, not just for real estate services, but for mortgage services and more,” says Move CEO Damian Eales. “This part of our business will evolve quite significantly in coming years.”

The Consumer

Mega-companies come with both opportunities and risks for consumers. Rocket, Zillow, and others see the opportunity to cut down on friction for buyers and sellers by uniting disparate parts of the housing ecosystem. “The more integrated the experience is, the easier it is to actually lower costs, and then pass on savings to the person who matters most, which is the consumer,” says Rocket’s Krishna.

That isn’t the way some left-leaning politicians see it. In a letter to the Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission, five senators including Elizabeth Warren (D., Mass.) and Bernie Sanders (I., Vt.) said that Rocket’s Redfin and Mr. Cooper deals “may reduce choice and raise prices for American families in the housing market” at a time when costs are already high.

“I couldn’t disagree more,” says Rocket’s Krishna.

No matter how a buyer purchases a home, it pays to consider the competition. Freddie Mac in 2023 said that borrowers who compared quotes from at least four mortgage companies stood to save as much as $1,200 a year compared with those who only sought one offer. “Sometimes the way these platforms work is they basically exploit impatient consumers,” says Columbia’s Van Nieuwerburgh. “It’s nice and it’s convenient, and they basically end up overpaying for that convenience.”

But bigger companies could also cut costs, particularly when it comes to home-building, says Van Nieuwerburgh. “There’s a huge number of very small construction firms that are frankly very inefficient,” he says. Deregulation efforts “could potentially lead to some much-needed consolidation,” resulting in more homes getting built—and more options for buyers.

As companies converge on similar visions of the user experience, they diverge on how it will be structured. Take private listings, for example: Advocates like Compass say sellers should be able to test the market before listing to the whole world, while critics like Zillow and eXp say such networks disadvantage buyers. The debate has split the industry down the middle, and is already changing the homebuying process. While Compass encourages sellers to list privately first, Zillow and Redfin have banned listings that aren’t immediately syndicated.

The industry’s evolution won’t stop with consolidation. “You finally have industry participants…all rethinking how things should work and criticizing existing processes that have been an afterthought for the past century,” says KBW analyst Ryan Tomasello.

Source: Barron's