- Ziggurat Realestatecorp

- Dec 3, 2025

- 5 min read

Every December, the Philippine state performs a familiar ritual. Government agencies release upbeat pronouncements on the affordability of the Noche Buena, complete with curated grocery lists, smiling inspection photos, and carefully rehearsed sound bites about stable prices.

These announcements follow a predictable script. They are designed to soothe public anxiety, create an appearance of control, and project an image of administrative competence.

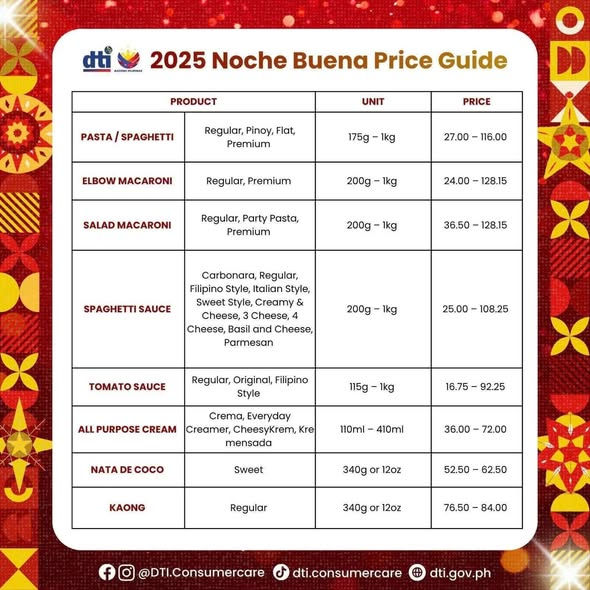

But this year, when the Department of Trade and Industry claimed that a family could celebrate Noche Buena with only 500 pesos, the public reaction was immediate and fierce. What was meant as reassurance turned into ridicule and outrage across social media, sari sari stores, palengkes, and dining tables. The backlash was swift because the number did not merely underestimate economic hardship. It underestimated the meaning of the season itself.

Filipinos were not angered simply because 500 pesos was unrealistic. They were angered because the statement felt dismissive.

It was the latest reminder that those in charge of economic policy seem increasingly detached from the realities of everyday families who navigate inflation not through spreadsheets but by rearranging their desires, postponing essentials, and sacrificing personal comfort for their children.

In short, the statement revealed a government out of touch with the emotional and cultural depth of the holiday it was reducing to a price point.

Spreadsheeting a tradition

To argue that 500 pesos is enough is to treat Noche Buena as a technical puzzle that can be solved by removing costly items.

Ham, queso de bola, fruit salad, spaghetti sauce, even bread. As long as one reaches the lowest possible total, the state suggests that the celebration remains intact and that a Filipino family should be able to produce a respectable Christmas meal.

Yet families know this is not how rituals work. The sociological value of Noche Buena lies in its emotional and symbolic weight. It is one of the few moments in the year when households attempt to suspend the relentless pressure of survival. Parents work overtime for ingredients not because these items are luxuries but because they help restore a sense of normalcy. They provide continuity with the Christmases parents remember from their own childhoods. They signal an effort to protect joy in an increasingly difficult world.

A fruit salad may not be essential for survival, but it is essential for memory. Ham may not be necessary for nutrition, but it is necessary for tradition. Spaghetti may not solve hunger, but it does create a shared moment of delight. These meals are not simply consumable goods. They are affective anchors that remind families of who they are, where they come from, and what values they want to hold on to.

When the state compresses this meaning into a 500-peso budget, it tells families to shrink their aspirations. It reframes celebration as a minimalist exercise rather than a cultural practice rooted in care, obligation, and continuity. It sends the message that the only valid celebrations are those that are cheap enough to justify.

Resilience is not public policy

The 500-peso claim is part of a larger political pattern. Philippine governance has long relied on moral narratives about the Filipino character. Industrious. Resilient. Resourceful. Patient. These traits, while admirable and often true, have been weaponized as political tools to shift responsibility away from institutions and toward individuals.

When inflation rises, Filipino families must adjust. When wages stagnate, they must budget better. When living costs increase, they must make sacrifices. In this narrative, the structural failures of policy become reframed as personal shortcomings. The burden is placed not on the systems that create hardship but on households that are expected to absorb its effects with dignity.

The 500-peso Noche Buena list is a perfect example. Instead of acknowledging that wages cannot keep up with prices or that agricultural policies remain weak, the state focuses on teaching families how to make do. It suggests alternatives, cheaper substitutes, and thriftier options. It treats poverty as an individual problem to be managed rather than a structural condition to be addressed.

Public frustration grows because people know their struggles are not caused by a lack of budgeting skills. Their struggles stem from an economy that no longer matches their hard work, from policies that fail to secure affordable food systems, and from governance that repeatedly asks citizens to stretch their resources while refusing to stretch its imagination.

When scarcity is the new normal

Beyond economics, there is a symbolic dimension to the issue. When officials insist on unrealistic numbers, they participate in what sociologists call symbolic violence. This is the imposition of a worldview that makes inequality seem natural, normal, or inevitable.

By stating that 500 pesos is sufficient, the state implicitly suggests that limited options should be accepted and that those who want more are unreasonable. Over time, expectations are lowered. A fuller table begins to feel like a privilege rather than a basic mark of care. Celebration becomes a luxury. Scarcity becomes a baseline. The slow erosion of expectations is precisely how inequality becomes entrenched.

This is why the public reaction was emotional. Citizens recognized the statement as an attempt to normalize the very struggles policymakers refuse to confront. They heard in the announcement not a practical suggestion but a political message: that the state is comfortable with how little families can afford.

The uproar reflects a deeper disconnect between policymakers and the daily realities of ordinary people. If government officials cannot accurately estimate the cost of a simple holiday meal, how can they be expected to design policies for wage adequacy, food security, or market regulation.

The issue is not pasta or ham. It is government credibility. When officials speak from a place detached from everyday life, they erode public trust in institutions that rely on legitimacy to govern effectively. A government that cannot understand the emotional logic of Noche Buena is unlikely to understand the needs of the households who live paycheck to paycheck.

As inflation continues to shape household decisions, people look for leaders who can speak honestly about hardship. They look for empathy. They look for clarity. What they often receive instead are holiday graphics, supermarket walk throughs, and unrealistic calculations designed to create the illusion of control rather than addressing the reality of struggle.

Why settle for survival?

In the end, the debate is not about whether a family can technically survive Noche Buena on 500 pesos. Under enough pressure, Filipino families have always found ways to stretch their resources. The real question is why the state continues to operate on the assumption that survival is an acceptable benchmark.

Public policy should uplift living standards, not minimize expectations. It should address food systems, wages, agricultural bottlenecks, and corporate pricing practices. It should confront, not obscure, the structures that make celebration feel like an economic burden. It should treat dignity as a non negotiable, not as an optional upgrade.

Filipinos do not ask for extravagance. They ask for the ability to create moments of joy without feeling punished by the economy. They ask for a holiday meal that reflects care rather than constraint. They ask for a government that confronts reality rather than performs optimism.

Filipinos deserve a state that does not ask them to shrink their dreams every December. They deserve leaders who listen before they prescribe and who understand that rituals hold societies together. They deserve policies grounded in empathy rather than assumptions.

A 500-peso Noche Buena is not just unrealistic. It is a reminder that the politics of pretending has gone too far.

Source: Rappler