- Ziggurat Realestatecorp

- Jan 18

- 4 min read

Global urbanization is entering a slower but more complex phase, and the Philippines is moving steadily toward a predominantly urban society that will be shaped by how well it manages its fast-growing cities. The World Urbanization Prospects 2025 (WUP 2025) combines new satellite-based data on built-up areas with improved population modeling, giving a sharper picture of where and how people are concentrating in cities, towns, and rural areas worldwide.

What WUP 2025 shows globally

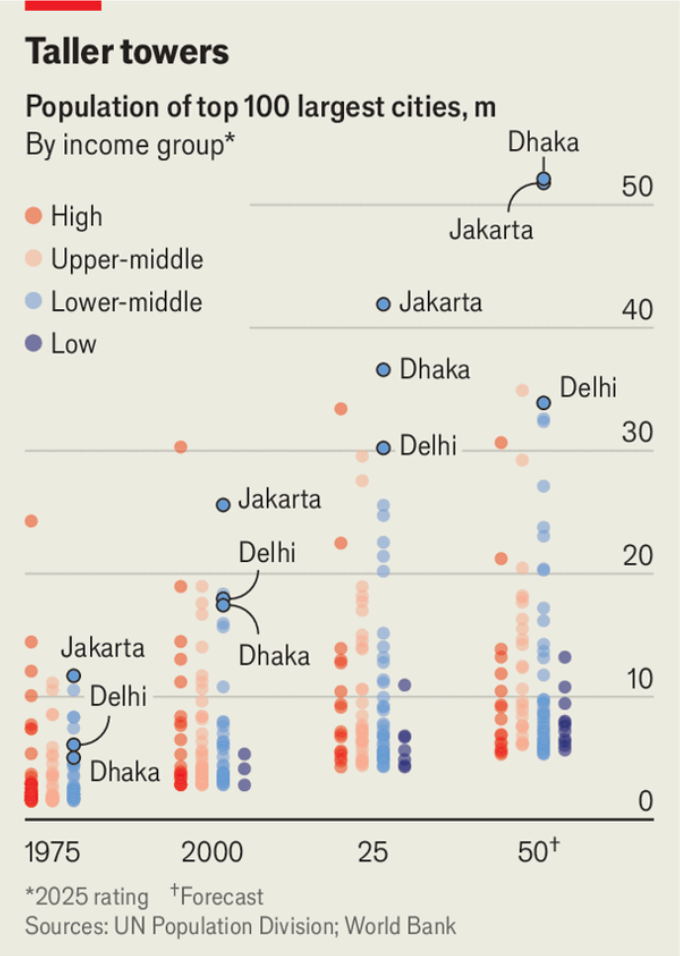

WUP 2025 confirms that the share of people living in urban areas continues to rise, but the speed of urban growth is slowing compared with the explosive expansion of the late 20th century. Growth is increasingly concentrated in low- and middle-income countries, especially in Asia and Africa, where a relatively small group of countries will account for most of the increase in city dwellers to 2050.

A major innovation in WUP 2025 is its harmonized “Degree of Urbanization” approach, which classifies cities, towns and rural areas using consistent thresholds for population density, size, and contiguity instead of relying solely on differing national definitions. This revision expands coverage to more than 12,000 urban centers of at least 50,000 inhabitants, allowing more granular estimates of city growth and the links between population, land use and built-up expansion.

Urbanization trends that matter

Several global patterns stand out. Cities’ built-up footprints have expanded roughly twice as fast as the world’s population since the 1970s, which means many urban areas are growing outwards faster than they are growing upwards, with implications for transport, infrastructure costs and environmental pressure. At the same time, many countries are seeing the emergence of dense small and medium cities that absorb much of new urban growth, rather than only a handful of megacities.

Future global urban growth will be heavily concentrated: just a few countries will account for over half of the nearly 1 billion additional city residents expected between 2025 and 2050, led by India, Nigeria, Pakistan and others in Africa and South Asia. This concentration raises the stakes for planning, since decisions in these rapidly urbanizing countries will strongly influence climate risk, resource use and inequality worldwide.

Where the Philippines is today

According to recent estimates that draw on the WUP series, around half of the Philippine population is now urban: about 49 to 50 per cent, or roughly 57 to 58 million people out of a total population of around 117 million in 2025. Urban growth remains positive but moderate, with annual urban population growth reported at about 1.5 per cent in 2024, which is faster than urban growth in many high-income countries but slower than in some of the fastest-growing African and South Asian nations.

The country’s urban system is dominated by the Manila urban agglomeration, whose wider built-up metropolitan area is estimated in the mid‑2020s at over 15 million residents, making it one of Asia’s largest megacities. But WUP 2025’s lower 50,000‑person threshold also highlights the growing importance of secondary and emerging cities across Luzon, Visayas and Mindanao, many of which are expanding in population and land area even if they remain far smaller than Metro Manila.

Snapshot: global vs Philippines (circa 2025)

Indicator (approximate) | World (2025) | Philippines (2025) |

Urban share of population | About 56–60% living in urban areas. | About 49–50% living in urban areas. |

Urban population growth | Slowing globally but still positive, concentrated in Asia and Africa. | Urban growth around 1.5% per year (2024 data as latest benchmark). |

Settlement pattern | Rapid expansion of built-up areas, many small and medium cities growing. | One dominant megacity region (Manila) plus a network of fast-growing regional cities. |

Key messages for the Philippines

First, the Philippines is on track to become predominantly urban in the coming decades, so planning for an urban majority is no longer optional; it is a demographic certainty. This means national and local policy must treat housing, transport, water, and social services in cities as core development priorities rather than afterthoughts, especially as climate risks like flooding and heat are amplified in dense urban environments.

Second, the pattern of growth matters as much as the pace. WUP 2025’s evidence that global built-up areas are expanding faster than population suggests the Philippines faces real risks from unmanaged sprawl around Metro Manila and other rapidly urbanizing corridors. Compact, transit‑oriented development, strict protection of high‑risk zones, and better coordination between land-use and infrastructure planning will be essential to avoid locking in congestion, high transport costs and vulnerability to disasters.

Third, secondary cities are an opportunity. With WUP 2025 now tracking thousands of smaller urban centers, the data underscore that dispersing economic growth into well‑connected regional hubs can ease pressure on Manila while improving access to jobs and services outside the capital. Strategic investment in mid‑sized Philippine cities—particularly in resilient infrastructure, digital connectivity and human capital—can create alternative growth poles that absorb population growth more sustainably.

Finally, urban policy and climate policy are increasingly the same agenda. The concentration of people and assets in Philippine cities means that progress on emissions reduction, climate adaptation, and disaster risk management will depend on how urban expansion is guided and how existing neighborhoods are upgraded. Using the richer spatial and demographic detail of WUP 2025 alongside national data can help identify hotspots where investments in resilient, inclusive urban development will yield the greatest long‑term dividends.

Source: Ziggurat Real Estate